When you’re called the best player ever, and your resume includes 16 Slams, a career Grand Slam, and three times you’ve won 3 Slams in a calendar year, you may forgiven delusions of grandeur. Roger Federer still believes. Still believes his game is good enough to win Slams. Still believes it’s his match to win or lose. Rafael Nadal was trained to think that unforced errors are a bad thing, but to learn that balance between aggression and steadiness, so that he doesn’t end up pushing the ball. This is the Spanish philosophy.

When you’re called the best player ever, and your resume includes 16 Slams, a career Grand Slam, and three times you’ve won 3 Slams in a calendar year, you may forgiven delusions of grandeur. Roger Federer still believes. Still believes his game is good enough to win Slams. Still believes it’s his match to win or lose. Rafael Nadal was trained to think that unforced errors are a bad thing, but to learn that balance between aggression and steadiness, so that he doesn’t end up pushing the ball. This is the Spanish philosophy.

Federer, on the other hand, is willing to take more chances. Federer’s game is rarely clean. He typically puts up many more unforced errors than his opponents. When his game is on, then he’s very hard to beat. He’s always looking to take a big shot and end the point quickly, and yet, he’s steady enough to avoid looking like a player ranked around 100 who does the same thing, but then hits 3 unforced errors in a row to lose a game. Eventually, one imagines, a player will come along that goes for big shots and makes it. The closest we have today is Roger Federer.

But being so good for so long, and believing that you can beat anyone in the world, even as they appear to have the upper hand–it’s a grand delusion. So when fans watched the fifth set between Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer, a match that looked like it might slip from Djokovic’s fingers for a fourth consecutive year, they saw a man that threw caution to the wind. When there was despair, at 15-40, double match point, Djokovic went for big shots. He didn’t play cautiously. He knew his game was good enough, and he just had to believe that his shots would go in. He hit inside in, then inside out, then Roger floated a high shot up, and Djokovic hit a swinging volley inside out for a winner.

30-40.

Then, Djokovic served again, and eventually got a deep middle ball, and ripped the ball crosscourt to Federer’s forehand, but out of reach. He later hit a drop shot that Roger chased down, he hit one passing shot, then a second down-the-line knowing a lob might lead to another tweener. And when he held at 5-all, Djokovic felt he had dodged a bullet, and he proceeded to break Roger in the next game then hold to win the match.

Did Federer sense that Novak took bigger chances at the biggest moments? No, he didn’t. Roger looks at his game from Roger’s perspective. He believed Novak is a talented guy, a guy who can make big shots, but Roger had match points, and that meant he had his chances. The win was on his racquet. To Roger, it’s not that his opponents played bigger. It’s that he didn’t hit the right shots at the right time, and that he has opportunities to do that. Roger clings to this belief strongly because it has served him well in the past.

But fans see it differently. They see that Novak, for once, fought his way out of despair. Fought his way out of the grips of the Swiss maestro. Made the big shots at the biggest times. Djokovic would joke that he hit those forehands as if he were blindfolded. He took a crack, and the ball landed in.

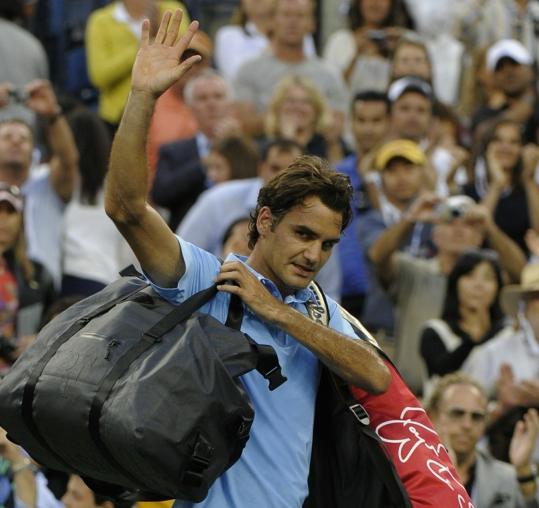

Federer, as always, went to the press conference. He answered the questions. He didn’t quite mention what was bothering him this time. There was a hint. There was a hint that even now, even after playing much better than Wimbledon where he’d hurt his back and leg, he said, where he’d been branded an excuse-maker, and less than gracious to his opponent, Tomas Berdych, that indeed, even here, at the US Open, something, however minor, was wrong.

In his mind, Roger loses because there’s something wrong. Sometime he overcomes it, and he doesn’t dwell on it any longer. Success through adversity. Sometimes, he doesn’t, and it seems the excuses, such as they are, give him solace that he can still continue to produce, still continue to beat the best players. Roger has learned to be gracious to his opponents, to Rafa in particular, but even, occasionally, to Novak. His sophistication dealing with the media sometimes seems a bit too practiced, a bit too refined, and yet just rough enough around the edges that you know that he’d rather say something far more saucy, far more Roddick. It doesn’t come across nearly like Nadal who, despite years on the tour, still speaks a broken kind of English, and that the humility in his interviews feels more genuine, whether it is or not.

Roger can go home, whether it be Basel or Dubai, or whereever in the world a multi-millionaire can truly call home, and he can say that his game is good enough to beat the best, but it’s not so good that there’s a guarantee that he will always secure the victory. For so long, writers have marveled at the perfection of his game, and yet, he does lose. Those pesky errors do add up. If he were as stingy with errors as Nadal, yet played the same game, Federer would have been a freak of nature, someone who went for big shots and always made it.

But Federer is, instead, a master of risk-taking, hitting the errors in selected spots, usually on the return game, so that he leaves himself less vulnerable. It is, in a weird way, a re-imagining of the serve-and-volley game. When you serve and volley, you know that some day, the opponent makes you dig out low volleys, forces a half-volley or you simply hit a weak shot and leave yourself completely vulnerable. You make a forced error, but it is forced, and you hope the odds work in your favor. You hope the attack leads to silly errors on your opponents and that you make more shots than you miss.

Federer has extended this philosophy to the baseline where he takes big shots even when it doesn’t make sense, and does it because he believes he can make just enough, just like the serve-and-volleyer, and that risk, if managed well, can lead to victories.

This time, it didn’t. Federer, as he did at Wimbledon as he must have done at the French, doesn’t want to be reminded he failed to seal the deal. He won’t watch the US Open. He won’t ask “what if”. He’s not so big a fan of the game that watching others gives him a thrill. He’s no Nadal who may look at a finals and enjoy it as a fan enjoys it.

And Federer will take time off, look for more answers, give himself more reason to think that age, the enemy of the good and the great, is not yet ready to take Federer down, that his opponents, with fresher legs and different skills, are not ready to claim themselves as lords of the tennis universe. He will continue to foster belief in himself, because that’s all Roger can do.

And some day, he imagines, that belief will be strong enough.

![[US Open Men’s Final] Can Djokovic beat Nadal in the finals?](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/20130909djokovic-500x383.jpg)

![[French Open] The tactics of the Djokovic-Nadal semifinals](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/20130607nole-500x383.jpg)