There are different ways to win a match. Some fans like offense. Back when Steffi Graf was dominant, she sometimes had to play Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario. Graf brought a new level of power to the women’s game. She was fast, had a big serve for the day, and the biggest forehand in the women’s game (at the time). Sanchez-Vicario was herself speedy, but she was more of a defensive counterpuncher, running down shots and keeping points in play. She won by getting another shot back. Needless to say, many fans didn’t appreciate her defensive style.

There are different ways to win a match. Some fans like offense. Back when Steffi Graf was dominant, she sometimes had to play Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario. Graf brought a new level of power to the women’s game. She was fast, had a big serve for the day, and the biggest forehand in the women’s game (at the time). Sanchez-Vicario was herself speedy, but she was more of a defensive counterpuncher, running down shots and keeping points in play. She won by getting another shot back. Needless to say, many fans didn’t appreciate her defensive style.

Today’s modern version of that is Federer and Nadal except that Nadal is quite a bit more offensive than Sanchez-Vicario. While Nadal is perfectly happy defending shots when an offensive player like Tsonga or Berdych or Soderling attack him, he also looks for opportunities to take a shot sitting in the center of the court and attack the shot. The purpose? It’s not to hit a winner, but to hit a shot which the defender can only just reach, but not be offensive with it. Pretty soon, Nadal has his opponent on the run, and then gets an opening and goes for the winner.

Andy Murray, by his nature, is more of a defensive player. While his offense has improved under Lendl, you see it more against weaker players or against Rafael Nadal. It’s a problem for Murray to be offensive against Djokovic because, ever since 2011, Djokovic has become something of a defensive juggernaut, becoming a wall much the way Nadal has become a wall. Federer learned this when he played Djokovic in the year-end championship in London when he just couldn’t hit through Djokovic. It was a humbling experience for the Swiss maestro.

The strategy against a player of Djokovic’s caliber has been to play long points and try to attack the Djokovic fitness. This is not an easy strategy as Djokovic has improved his fitness considerably since going to a gluten-free diet. Prior to that, Djokovic struggled when playing under heat and had retired numerous times in Slams. Some commentators joked that he was well on his way to a Grand Slam of retirements having retired in 3 of 4 Slams.

Let’s break down some of the things that worked for Andy Murray.

The heat

Europe had been unseasonably cool from the French Open through the start of Wimbledon. As such, much of the training players do at the start of the year to deal with the heat of the Australian Open had kinda worn down. The finals of Wimbledon was a balmy 85 degrees, the hottest it had been all tournament long. While Melbourne and even New York can get much hotter, players expect the heat at those events and prepare accordingly. Rain and cool weather is typical of Wimbledon, not heat.

Having said that, both players seem to struggle in the heat, but because Murray played drawn out points from the start with long 20 shot rallies common, and Djokovic appeared to be affected by the heat earlier on. His eyes glazed. He tried to serve and volley to keep points short. He was more offensive off the ground trying to take out Murray’s legs.

Juan Martin del Potro

Gotta say it. Juan Martin del Potro did Murray a favor in last year’s Olympics where he pushed Roger Federer to a 19-17 third set. Although the finalists got a day off, Murray came out firing and Roger Federer looked less than sharp in his drubbing in the gold medal match.

This year, Djokovic was pushed to nearly 5 hours of play by del Potro, the longest in Wimbledon history. Other than the numerous dives Djokovic took on the slippery grass, he seemed reasonably fit, but perhaps that match, combined with the heat lead to Djokovic wanting to keep points shorter. Djokovic had come back from really long matches to play really long finals (at the Australian Open final in 2011). Admittedly, the Australian Open is played often late in the afternoon heading into darkness, so the lack of sun helps a player work through the length of match. Meanwhile, Wimbledon is played in the early afternoon, which is usually the peak of heat.

Murray’s serve

If Murray has one weakness in his game, beyond a predilection to passiveness, it’s his serve. It’s not just his serve, but his first serve percentage. While players like Roddick, Federer, and Nadal comfortably serve in the low 70% mark, Murray often struggles at about 55%. This, combined with some passivity, used to mean Murray had to play longer matches than his rivals who would win more easily because they were more offensive.

Since working with Lendl, Murray has worked to move his serving north of 60%, and he was able to achieve 65% for the match. This meant his normally weak second serve where he typically wins about 40% of the points was under less pressure. He was able to win about 70% of the points on first serve which is good, though not great, partly because Djokovic is such an effective returner and competitor.

As expected, Murray was unable to hit as many aces as he did against Janowicz, finishing the match with 9 aces, compared to 20 in the semifinals. Of course, that was a 4-setter, but even so, he averaged more aces per set and held more comfortably in more games against Janowicz.

Even so, Murray hit 9 aces, and he had a few comfortable service games, especially as he was closing out sets 1 and 2 where Djokovic seemed to offer no resistance.

Return of serve

When Murray played Djokovic in the Australian Open finals this year, he was unable to break Djokovic. Indeed, he only had 4 break opportunities the entire match. Whatever Murray’s faults were during this Wimbledon, breaking serve was not one of them. Murray often gave himself plenty of chances to break, but often suffered from being broken himself.

Murray’s return game gave him numerous chances to break, including the very first game of the match, where he had Djokovic down 0-40, before Djokovic reeled off 5 straight points to win the game. Murray would break Djokovic 7 times to Djokovic’s 4 times. In particular, Murray broke Djokovic early in the first set, only to get broken back himself, then he broke once again to take the lead for good.

Djokovic averaged only 60% points won on first serve. A typical number for a top player is often closer to 80%, and for players like Isner or Federer, it can reach as high as 90% points won on first serve. At 60%, Murray was getting good looks at many games. Worse for Djokovic, that number is only as high as it is because he was winning 70% of first serves in the second set, his best set. He was 54% in the first set and a paltry 52% in the third set.

The return was huge for Murray. While Djokovic would pressure Murray off the ground and engineer breaks, especially in the middle of the second and third set, Murray would come back and not only break to even up the match, but break again to get the lead. In both sets 2 and 3, Djokovic was up 4-2 and in both sets, he was broken twice, unable to push the set into a tiebreak.

Murray’s return combined with Djokovic serving somewhat lower first serve percentage than usual lead to Djokovic having to fight in the majority of games he served. He had a few easy games, but many were contested.

Djokovic unforced errors

Djokovic wanted to be more offensive in this match, both due to the long del Potro match, but also due to the heat, and the kind of long grinding matches he had historically played with Murray. Djokovic has, it seems, decided that while he can play long rallies, he probably shouldn’t, so he can lengthen his career. Federer, by contrast, tries to keep points short, even at the expense of making more errors. It suits his temperament, but it’s also done to extend his career.

To that extent, Djokovic came to net more, he tried moving the ball around more than Murray, but with the heat bothering him, he made more errors than usual in an attempt to keep points a bit shorter. Indeed, he made twice the number of errors than Murray: 40 errors to Murray’s 21. Some of this may have been a hangover effect from playing del Potro where his normally pristine shots went a bit awry, which helped del Potro win more games and ultimately push Djokovic into a fifth set.

Retrieving drop shots

Because Djokovic was dictating play more than Murray, Murray was doing a lot of running, more than Djokovic. By the third set, Djokovic was wondering whether Murray’s legs were starting to go and began to drop shot. It was effective at the start as Murray seemed bother by his quads. However, it didn’t hurt Murray that his semifinal opponent was Jerzy Janowicz.

The big server probably helped in two ways. First, with his big serve, Murray learned to track a very fast serve. Djokovic, by comparison, had to look more like a melon, an easier target to hit. Second, Janowicz drop shots more than anyone on tour, so Murray had to fetch many drop shots. Janowicz was initially successful, but Murray grew increasingly adept at getting those drop shots.

In the last break of Djokovic’s serve, Murray was able to get two short balls and hit them for winners, and it eventually lead to a break of serve.

The crowd

The British public has often been polite to a fault. Good sportsmanship and all. Even when their player wants the crowd to resemble a football (soccer crowd), having upper class audience who find it offensive to act like the riff-raff makes it tough to get that home court advantage. Some feel this should be the gold standard by which audience behavior is met. Even some relatively benign cheering of double faults were perceived by some as bad behavior. Consider how many a basketball game have fans jeering “air ball, air ball” when a basket is missed.

Indeed, if you find a video of the semifinals between Djokovic and Murray in the Olympics, you’ll see a far more rowdy crowd that stayed noisier throughout, making the match seem more like a Davis Cup tie than a Wimbledon match. The crowd was generally reasonably fair given many wanted Murray to win. The occasional “Come on, Novak” could be heard from the audience, and they were generally quiet during the point, with the exceptions of oohs and ahhs.

But as Murray hit nice points, they would cheer in between points, and that had to help Murray who was urging the crowd to support him.

The slice

Throughout the last two matches where Murray was being peppered by bombs from Verdasco and Janowicz, the slice backhand kept him in long points, so he could buy time, and give his opponent another chance to make a mistake. Murray’s always had a very nice slice backhand, especially for a two-handed player, but he used it extensively against Djokovic either to buy time, or to give a variation on the topspin hitting. At times, Djokovic was thrown off by the slice.

Using a middle strategy

Murray decided not to go for risky shots. Given the choice of going for a winner, or hitting a hard shot that was safely in the middle, he opted for the second. He wanted to hit with enough power to prevent Djokovic from controlling the point without going for winners. Djokovic, by contrast, wanted to move the ball around more, hitting angles to the backhand, hitting angles to the forehand. Murray wanted Djokovic to take that initiative.

As Murray frequently hit deep to the shallow backhand, Djokovic would alternate hitting down the line, and hitting inside out or using his angled backhand to the Murray backhand. This often left Murray scrambling to retrieve the backhand, which in turn lead Murray to running more, but it was more of Murray daring Djokovic to keep hitting bigger, and Djokovic mostly obliged because he didn’t want to play longer rallies, even as he played longer rallies.

Using the grass

Of course, Murray did hit the occasional winner, with the idea of hitting behind Djokovic, a strategy that worked well for del Potro. As good a mover as Djokovic is, and as worn down as the grass had gotten,

Fighting off break points

The mark of a champion isn’t so much how hard they hit, but how well they defend break points. The best players do an incredible job of fending off break points. Murray had broken back a second time after being broken himself, and found himself in a 15-40 hole, but he managed to get himself out of this hole, and hold serve, which was key to taking the first set.

To be fair, Djokovic also had at least 2 games where he fought off break points, including the first game of the match.

Nowhere was this more important than when Murray served for the match and got up 40-0. Djokovic played a brilliant point at net to get to 40-15. Then, he played an aggressive return which Murray couldn’t reach to reach 40-30. Murray hit a backhand long for deuce. Then, he dumped a shot into the net for break point. Murray would hit a good serve that Djokovic returned deep to get back to deuce. Djokovic would hit a half volley that tipped the net to get it to his ad. Murray would save once again, and Djokovic would get to break point once again. Finally, Murray strung together 3 straight points. The final point was a serve out wide, with a deep return to Murray’s forehand. A woman gasped as she thought it was sailing long, but it went in.

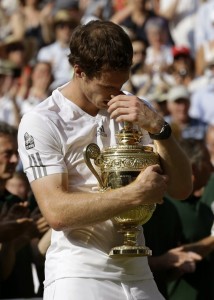

Murray hit an inside out forehand to the Djokovic backhand. He went for a shot down the line, but clipped the net, and that was how Murray won Wimbledon.

Conclusion

Did Djokovic play the best tennis? He struggled on serve and with unforced errors, but he hit enough good shots to give him a chance, and he had breaks in both second and third set. Because Djokovic wanted to play shorter points due to the heat, he ended up making more errors. Meanwhile, Murray avoided playing ultra-aggressive tennis. His goal was to play long grinding points and play shots that would keep him at neutral, making it hard for Djokovic to be aggressive without taking a chance. Murray also waited for Djokovic to be the aggressor whether it be by responding to drop shots or by hitting hard crosscourt forehands when sent wide right. Murray played with enough aggression to hit a few nice shots, but used the Nadal model of not going for winners so he could keep his unforced error count low. It’s not the sexiest way to play. Fans might prefer the aggression of Federer that opens up the court for winners.

Fans have always appreciated offense more than defense. It takes a knowledgeable fan to appreciate defense because it relies on opponent’s errors. When given the choice to take control of a point, or to help the opponent make errors, fans prefer the glitz, unless, perhaps, the errors are caused by a finesse game of lobs and drop shots.

It would have been a rarity in tennis for a player that has reached as many Slam finals as Murray has (six) and not win more than one Slam. Lleyton Hewitt reached 4 Slam finals and won two. Marat Safin reached 4 Slam finals and won two. Pat Rafter also reached 4 Slam finals and won two. Goran Ivanisevic reached 4 Slam finals but only won one, all at Wimbledon.

Murray has reached the fourth consecutive Slam final that he’s played in (since he skipped the French), plus two more before that. Under Lendl, Murray has been as successful as he’s ever been, breaking through at the Olympics, then at the US Open, and finally at Wimbledon.

He changed his style from a finesse style built on retrieving and anticipating shots, to a more aggressive mode, and against players like Djokovic, he found a style that was more wearying than dazzling, but it was this style that helped him to the victories he’s had so far, and in the end, he gave himself plenty of opportunities to win breaking Djokovic more times than he had been broken all tournament long by all his previous opponents combined.

Murray came in as a kind of underdog, with the weight of a nation on his shoulders. He found opportunity, battled his mental demons, and found ways to win. The desire to fight when things looked its most desperate is a trait that many a British player, perhaps too dainty in personality, lacked. It took a rough around the edges Scot with the intellect of Ivan Lendl to break through history’s most daunting obstacle and to change the last man to win Wimbledon since 1936 to the last man to win Wimbledon since 2013.

The era of futility was recognized decades ago when Monty Python had a sketch of the blamanges from the planet Skyron in the galaxy Andromeda who changed all of England to Scotsmen, known as the worst playing tennis country in the world, but the lone Scotsman did win the title.

![[US Open Men’s Final] Can Djokovic beat Nadal in the finals?](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/20130909djokovic-500x383.jpg)