This must seem like old hat to Roger Federer. This is Roger’s 22nd Slam final and his eighth consecutive final. The record for consecutive semifinals, after Roger, was 10, by Ivan Lendl.

This must seem like old hat to Roger Federer. This is Roger’s 22nd Slam final and his eighth consecutive final. The record for consecutive semifinals, after Roger, was 10, by Ivan Lendl.

At this point, Roger knows how to play the game, and that’s not just the game on-court, but the game off-court.

There could be no bigger difference between a player and his biggest rival than Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal. Nadal’s English, while serviceable, allows Nadal to be the shy guy in interviews, to be endlessly complimentary to everyone around him. Interviews indicate Nadal always listens to Uncle Toni, doesn’t backtalk to him. Uncle Toni would have it no other way. It’s a sharp contrast to his play on court which is doggedly determined. The snarl of his upper lip is his most common tell, indicating he’s just a bit annoyed with how that last point went. Nadal is the good son, or maybe good nephew, not exactly what you’d call a gentleman because he lacks that suave, that sophistication. That make his diffidence a bit disarming and surprisingly sincere.

Roger Federer, on the other hand, exudes the idea of gentleman, indeed extraordinary gentleman. Let’s just begin with languages. Where Nadal struggles to conduct interviews in English, a skill he’s getting better at each year, Federer speaks English as a first language, a product of his mother’s South African heritage. We all know Switzerland is a tri-lingual country. Not everyone speaks the languages there that include French, English, and two flavors of German. Federer can go to the French Open and give a speech in French, and play in Hamburg and conduct interviews in German. Perhaps if Jim Courier’s Channel 7 gig ever takes him to Paris, he can conduct an interview in French, a language he picked up over the years, with Federer.

But Roger wasn’t always this way. Once upon a time he was a superbly talented athlete, a highly emotional, often argumentative player. He knew little about how to play tennis for the long haul, how to be fit, how to move, how to eat, how to control his emotions. Roger almost had a dilemma on his hands. Growing up, Roger idolized the serve-and-volleyers, especially players like Pete Sampras. He modeled his game on that style. It had been years since a top serve-and-volleyer wasn’t a serviceable baseliner.

Although Sampras increasingly played serve-and-volley as he got older, mostly, one imagines, to preserve his delicate physique (Agassi, perhaps due to the ups-and-downs in his career, was far more durable) and to avoid the grind of baseline rallies. Even so, he was more than an adequate baseliner. He was no Tim Mayotte or Pam Shriver, players that were nearly helpless at the baseline and had little choice but to come in. Tim Henman, for instance, was just at that transitional point. A serve-and-volleyer yes, but not a good enough groundstroker, to dominate off the ground. Still, in a pinch, he could play from the backcourt.

The revolution of modern racquets and modern strings didn’t begin to truly impact the game until the late 90s when the passing game went through the stratosphere. Classic tennis teaches us that short tennis balls are to be attacked and approached on. And for many decades, those who had a net game, did this. Even players that were pegged as baseliners, such as Jimmy Connors, routinely came to net.

Ancient film of tennis played in the 1950s shows that when an attacker came to net, the baseliner, who hit a flat shot, was often left lobbing the ball up, worried they could not pass reliably enough while under duress.

But that began to change with players like Andre Agassi and even Pete Sampras. Today, an approach to the net had better be really good because players will now stick out their racquets and thread the ball through the thinnest possible margins, and do it time and again. This play, combined with the near complete migration of players from one hand on the backhand to two has made everyone fearful of coming to the net.

And it was during that period of passing excellence that Roger found himself playing. Early in his career, he had to contend with his two biggest rivals, Lleyton Hewitt and David Nalbandian, both formidable baseliners. Against both these players, Roger felt he had to come to net because he just couldn’t beat them on the baseline. Today, the idea of Roger being afraid of Lleyton’s groundstrokes seems rather quaint. Hewitt was more like a souped-up Chang or Wilander, a player that had good movement, could move the ball around, but wasn’t going to pound for winners. His game worked out well against an aging Sampras, but was more like Connors or McEnroe playing in the 80s–they played a style that was going out of fashion, still effective, but not the trend that Borg, then Lendl set into motion.

Unlike the wunderkinds of the past, players like Chang, Wilander, Borg, and Becker, Federer didn’t start to make an impact in the sport until his early 20s. He had, of course, beaten Sampras on grass back in 2001, before he turned 20, but he wasn’t really mentally, strategically, or physically ready to handle the kinds of players of the day.

One day, when tennis historians really take a look at how the game changed, they will point to Ivan Lendl. Considered robotic, argumentative, with a habit of spitting between points early in his career, Lendl was the first to push the envelop of tennis preparedness. He worked on his fitness off-court. He controlled his diet. He had Warren Bosworth customize his racquets to produce uniformity that modern tennis factories could not achieve. He had his courts by his Connecticut home resurfaced by the same people that resurfaced the US Open. Many of Lendl’s training habits, seeming taken from the future, became the staples of modern pros. But as with any pioneer of the sport, there are always people ready to push that level even further.

And that man is Roger Federer. Federer’s training habits are largely kept secret. He’s not interested in his rivals learning how he does what he does. Federer used to have coaches that traveled with him. There was Peter Carter, who died in a car accident, and was Federer’s first major personal loss. There was Peter Lundgren who eventually coached Marat Safin. And on a part-time basis, he worked with Tony Roche (who coached Lendl for many years) and Jose Higueras (who coached Jim Courier). Since Higueras, he’s only made one additional overture, to Darren Cahill, for coaching. Cahill declined.

Federer travels without a coach, these days. He consults on strategic matters with Davis Cup coach, Severin Luthi. His fitness and strength are handled by Pierre Paganini who has helped Federer get strong, learn when his body is telling him he is injured, teach him how to move and recover quickly while maintaining balance. To this end, Federer often skips out on Davis Cup realizing that his future fame is not built on Davis Cup ties but on more Slam wins. During the December break, Federer often trains in Dubai working in the heat, to better prepare himself for playing in the heat of Australia.

Beyond that, Federer has worked on his mental toughness, though there is little information on how he does this. Federer often talks about working his way into the tournament. In matches he struggles, he rarely betrays that he is worried. He understands matches can turn on a lull in a player’s concentration, and he feels supremely confident that he can take advantage in those moments. Nowhere was this more in evidence than his victory over Andy Roddick in last year’s Wimbledon where he only broke once, but the one time that mattered. So where observers note Federer was struggling against Andreev, Federer thinks he was not. He rarely elaborates why he thinks this.

If anything, it shows, even when his game is not on, Federer learns not to panic. He knows, typically, in time, his game will come around, that he will play better.

Of course, you’d imagine, with all this advanced training technique, both physical and mental, that Federer would dominate his opponents, and while he clearly does have an advantage, at times, his game does break down, and he does cede the mental edge, and there are players that hit shots that are hard for Federer to handle, players like Nadal and del Potro and Davydenko. Sometimes all that planning still doesn’t work out as well as you’d like, but much like Lendl, you try to take care of what you can, and invariably it leads to more matches won than lost.

At age 22, Andy Murray has yet to win his first Slam. He reached the finals of the US Open in 2008, but quickly got buried in the first set by Federer’s aggressiveness. Murray had played Federer well historically, even then. He’d often keep the ball in play until Federer self-destructed or just missed a bit too often. That day, with Federer having had an extra day of rest, and Murray having played three days in a row (albeit two sets on two days, but even so), Murray had few answers. Perhaps a critical non-call in the second set on a Federer ball that was out that would have meant a break and a possibility for Murray to claw his way back in the match. As it was, once Federer took the second set, he cruised to a win.

Murray, too, was once like Federer. A talented player who struggled with fitness and movement. Where Federer might get upset in his early years, Murray tended to get annoyed and have a bit of a temper. His game would dip down. Murray showed his prowess in playing when he took Nadal to a fifth set in the Australian Open several years ago, but faded in the end when his fitness wasn’t up to snuff.

Since his departure from Brad Gilbert, he’s worked on strength, fitness, and strategy with “Team Murray”. His team includes coach Miles Maclagan, trainers Jez Green and Matty Little, his physio, Andy Ireland, and his coach-consultant, Alex Corretja.

Where Federer’s training techniques are mostly secret, Murray has been a bit more open about his own training. He doesn’t reveal everything he does, of course, but he’s put out the occasional video during his Miami training sessions. He has also embraced Twitter, tweeting about various dares (which he calls forfeits) that his team has to endure, often doing silly things like wearing dresses to dinner. This may be a totally PR thing to offset the negative image Murray had had in his early career.

Murray’s approach to the game is far different from Federer’s. Federer has a more Lendl-like approach to the game. Be aggressive from the baseline, have a variety of shots to deal with difficult situations, and try to dictate play. When his game is on, as it was with Hewitt and Tsonga, Federer often looks unstoppable. Federer’s game is built on rhythm, playing a series of pressure points for as long as possible, hoping the deluge of great shots will not only net him games and points, but also produce psychological victories, making his opponents wonder how they will beat him. Federer sees the winning of the game internally, from his ability to dictate the flow of the game, yet he’s smart enough, resilient enough, to keep his head in the game even when his plans are not going so smoothly.

On the other hand, Murray’s approach resembles that of his former coach, Brad Gilbert. He’s taken Gilbert’s philosophy of winning ugly and made it beautiful, in his way. Murray has three big strengths. The first is his anticipation, which leads to his second strength, his return of serve, and his third strength, his speed to reach balls. Murray often stands many feet behind the baseline, and uses a mix of slices, slow topspin, hard topspin, and drop shots, to upset the normally steady rhythm players see from everyone else.

This approach to the game requires a kind of maturity that is seldom seen. Think about it. Would you prefer to hit like Fernando Verdasco, blasting balls anywhere on the court, but making tons of errors, or would you prefer to play like Lleyton Hewitt, scrambling around the court, making shot after shot, but never quite having that knockout punch? Young promising male juniors are often guilty of loving topspin and power above all. To play a style of game where you try to disrupt someone’s playing rhythm and goad them into errors? That’s way too brainy an approach, and seemingly not very fun.

The contrast between Andy Murray and Roger Federer is much like that of Mats Wilander and Ivan Lendl. Lendl was about trying to blast a player off the court. Over time, he did give his game nuance, relying far more on the slice backhand to diffuse players like McEnroe, and learning how to serve and volley. Wilander was not the hardest hitter in the game, but he was smart. Folks routinely said that Wilander’s biggest weapon was his brain.

Both Murray and Federer are far more skilled than Wilander and Lendl. Lendl, for all his preparation, never looked elegant and graceful, something Federer gets complimented on all the time. Wilander never had the kind of touch Murray has, nor his footspeed and anticipation.

Murray has not only embraced some of the training that had made Federer successful, but even his mental outlook. Although he sounds like a broken record, Andy Murray has come out saying he can beat Roger Federer. Of course, what else should he say? In that approach, Murray resembles Federer more, and Nadal less. Nadal, for example, was perfectly happy saying that he didn’t care about number 1, and didn’t even much care about winning the Australian Open. Were he American, he might be lambasted for not being competitive enough, for not saying the right tough words.

So that leads up to this match. Already, Roger Federer is starting on the mental warfare. In an interview after his pummeling of Tsonga, Federer said that Murray had pressure to win the first set, to win his first Slam, to win for the British empire. Federer, well, he’s had a bunch of Slam titles. He doesn’t want to lose, but there’s little pressure for him to win another Slam, and therefore, he posits, he can play more carefree.

Federer’s more likely to play such mind games against his opponents, and it may say something about his respect for Murray’s game that he feels the need to do this. He’s careful to give praise here and there. Seemingly beneath his cheery demeanor, there’s a resentment that Murray gets all this positive press and has yet to win a Slam. In his mind, someone like Roddick should get more props for his one Slam and for continuing to fight it out.

Murray, for his part, has not joined in this verbal joust. It makes sense for him not to get involved. Federer is right, after all. He’s the one with the lengthy resume, not Andy Murray.

Much like the Nadal match, this match’s outcome seems very much determined by the tactics Andy Murray will use. Given his major rivals are likely to be Nadal and Federer for a while, Murray and his braintrust have likely spent a good deal of time working out a way to play Federer. Historically, Murray has used his variety to upset Federer’s rhythm. Lately, Federer has taken to attacking Murray more especially on second serves which is still a Murray weakness. Murray has beefed up his first serve the last two years, but he lacks the same kind of consistency that Federer has.

If someone is likely to play in a surprising way, it’s more like Andy Murray than Roger Federer, though it’s not clear what that strategy would be. For all of Nadal’s considerable skills, he plays in a defensive manner, perhaps the most offensive defensive player there is. Nadal has a great deal of patience, and often chooses to hit another ball rather than jump at a chance to go for a winner. This gives Murray opportunities to play more aggressively knowing Nadal isn’t likely to get into a bashfest with Murray.

Federer, on the other hand, is a more aggressive player. He relies more on his serve to set up his game. He wants to open up either an inside out forehand or an inside in forehand. Lately, he’s tossed in the occasional drop shot to change things up. Like many other top players, including Andy Roddick, Novak Djokovic, even Nikolay Davydenko, Federer wants to approach the net more often. Andy Murray is also trying to do this more. One surprising strategy Murray took against Rafa was serving and volleying. He almost always did this on wide serves to the Nadal backhand in the deuce court, knowing Nadal would slice the return back.

Federer will also use his trusty slice. The slice backhand was the one wrinkle that Federer used to dominate the game a few years ago. He would hit shorter slices that would draw his opponents into the court, then hit hard, as they were backpedalling to the baseline, hoping to elicit a weak shot which he could pounce on. Now that he’s used this strategy for a while, players are mostly wise to it, and have come up with ways of handling it.

Ultimately, the match will probably come down to how well each player serves and returns. These two strokes start off the point. With a good start, one player or the other can dictate rallies. Mental toughness will also play a big role. One player may take quick advantage. The other has to weather the storm and continue to play well despite either not hitting well or despite the opponent hitting well.

The final is, in my mind, more intriguing than if, say, Nadal had reached. If Nadal had made the finals somehow, Federer would likely be favored. Of course, it depends on how Nadal reached the finals, but given how he’d played this tournament, he’d probably have had some tough matches and not looked that good. Meanwhile, at the very least, Murray seems in really good shape, having prepared as well as he can, and so other than the odd tweak on his back, he seems as ready to win this tournament as he ever has.

He just has to get past Roger Federer. And Roger has other plans.

Hope this is a great match!

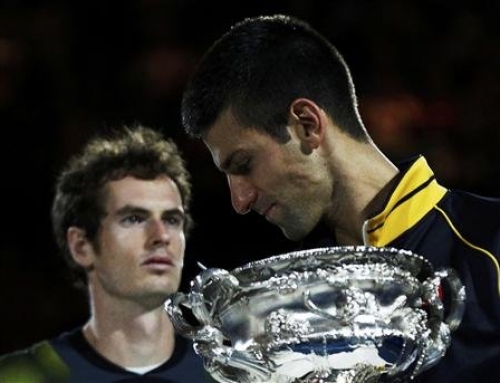

![[Aussie Open Final] Can Andy Murray beat Novak Djokovic?](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/20130126andy-500x383.jpg)

![[Day 13, Aussie Open] Bryan brothers win 13th Slam with Aussie doubles title, Kyrgios wins boys title](https://www.essentialtennis.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/20130125bryan-500x383.jpg)