By Jacob Funnell

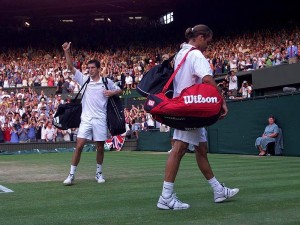

“We’re in a situation that if we don’t take In 2001, there was little indication that the era of serve and volley tennis was living on borrowed time in its spiritual heartland of Wimbledon. Players at every stage of their career, and of every stature, were following their serves into the net with great effect. The mighty Sampras and the ever-hopeful Henman, the giant veteran Ivanisevic and the rising star Federer, all used the same basic game plan. Whether following booming 130mph serves, or more modest deliveries, there could be little doubt which style was ascendant on the skiddy, low-bouncing grass, with Andre Agassi the only baseliner in the semi-finals. Wimbledon 2001 is especially famed for being the first and only time Sampras and Federer met competitively. Of course, they would go on to meet each other eternally, in the unwinnable game of ‘Who is the Greatest Tennis Player Ever’. It is obviously wonderful to watch Federer at a time when all the world could have scarcely guessed the towering heights of his dominance to come. Another remarkable aspect of the match, however, is the style of both men. Federer was very like Sampras. He served and volleyed, and though his serve lacked the venom of Sampras’, these minor details were outweighed by the great similarities between the two as they vied for control of the net. Federer went on to lose to the serve and volley of Henman, who went on to lose to the serve and volley of Ivansevic, who went on to beat the serve and volley of Rafter, to win the title. This was not to last. The balance between serve and volley and baseline tennis would be tipped decisively, and in 2002, now Tim Henman was the only serve and volleyer in the semi-finals. Hewitt and Nalbandian went on to play the first Wimbledon final without a single player attempting the tactic, even as a surprise change-up. Even Agassi would serve and volley as a change of pace, a different look, something else for the other guy to think about. Now Wimbledon was winnable without even needing to do it. The factors for this change go down like accessories to murder in the minds of many tennis fans. What were they, then? What had turned the attacking game of serve and volley into endless metronomic rallies[1]? Before all else, tennis players themselves have changed. Nobody would doubt that the current top 20 is fitter, faster and stronger than at any point in history. In 2011, the world’s best serve and volleyer, Michael Llodra (ranked 24th), hit a heavy kick serve, in the deuce court, to the backhand of the world’s best baseliner, Rafael Nadal (ranked 1st) on the ‘quick’ clay of Madrid. Nadal, standing about 10 feet from the baseline, hit a backhand crosscourt, dropping relatively tamely at Llodra’s feet. The great touch-artist half-volleyed the ball at a sharp angle away from Nadal, bouncing very close to the net of Nadal’s ad court service box. To even reach the ball before it bounced twice would require dashing across almost the entire diagonal of the court at four-fifths the speed of an Olympic sprinter. This is exactly what Nadal did, covering 15 metres in less than two seconds, before deftly dinking the ball past a helpless Llodra cross-court. The changes in racket equipment at the turn of the century had their impact, too. Often cited as a seismic shift in tennis, Gustavo Kuertern started using underwear elastic company Luxilon’s polyester strings in 1997, and went on to win three French Opens. With these strings the ball gained more spin and speed when hit with the ferocious racket-head speed generated by modern, ‘windshield wiper’ swings. Taylor Dent, who continued to serve and volley deep into the 2000s, considers modern strings the main culprit for its demise[2] “I think that the biggest changes are in the strings, that’s actually a bigger change than from wood to graphite, because these guys can get so much dip on the ball at such a high pace. In the past, if you were serving and volleying, it was really tough for the guy to get a return down at your feet because you can’t generate that kind of spin off a first serve. Generally speaking, you’re just trying to keep it low over the net, but now, if you don’t really stretch a guy out, it’s coming back at your feet, and then they can hit passing shots so hard because they can generate so much spin.“ Furthermore, going into the 2000s were the first generation of tennis players who had played with graphite rackets since the age of 4 or 5. It became second-nature to them to use these new, powerful tools, whereas in the previous era many top pros had made this change mid-career. But though this change in technology certainly made life no easier for serve-volleyers, how to explain their disappearance even from the quick lawns of Wimbledon? Well, they became less quick. And it is this change, above all, which is lamented by modern professionals. As Greg Rusedski remarked mournfully at Queen’s Club 2008 whilst commentating on the wholesale destruction of serve-volleyer Jonas Bjorkman by Rafael Nadal “these aren’t like the grass courts we used to play on”. The change in grass courts is such that all talk about serve and volley being the ‘ideal strategy’ for the surface is antiquated. Unlike the changes in racket technology and the fitness of the players themselves, this was a step-change. Allegedly motivated by a desire to lengthen rallies, due to the increased television spectator revenue promised by longer points, Wimbledon 2002 was utterly different to Wimbledon 2001. The substrate of the courts were changed to encourage higher bounces. The mix of the grass changed from a quick 70% Rye / 30% Creeping red fescue, to a slower 100% Perennial ryegrass. This, coupled with the slower balls[3], led to one thing – the first ever Wimbledon final that lacked a single serve and volley point, between the straightforward baseliners of Hewitt and Nalbandian. Federer further notes that “unfortunately, they’ve slowed down everything, indoors, grass. Everything has become so slow, I think that is a bit of a pity.” After this conspiracy of factors had successfully killed the last great serve-volleyers, what remains of serve and volley going into the new decade? At the highest level, only three players consistently in the top 10 serve and volley regularly, in that they will serve and volley at least once in most matches. Those are Federer, Roddick and Murray. All three men have great variety in their shots and game plans. Federer idolized Edberg as a boy, and his attacking instincts, obvious enjoyment of the style, and practised technique, mean that he (comparatively) often serve-volleys, especially when comfortably in front, or when playing in practice/exhibition matches. Roddick, by contrast, has no apparent love of the serve and volley game. He does, however, have a love of serving, and a tireless desire to try new strategies against any opponent. Thus, when Michael Llodra began chipping his giant serve back during Wimbledon 2010, Roddick began to serve and volley to force the Frenchman to go for more risky shots. And during the ATP World Tour Finals the same year, he came up with the daring tactic of serve-volleying on his second serves against Nadal, the rationale being that this was his best approach shot. It paid limited dividends, but the tactic remains a viable weapon in his armoury. Murray is naturally fond of variety, and though this primarily means differences in his groundstrokes, he will occasionally change-up play with a serve and volley point. Temperamentally unsentimental, he will happily serve and volley when it works, as his fine use of serve and volley against David Nalbandian in the 2010 Paris Masters demonstrated. Down a set and losing badly from the back of the court, Murray switched to serve and volley tactics. This game-changing decision saw his play likened to that of Boris Becker and Pete Sampras, and he went on to take the next two sets to win the match. Providing more support for the view that slower court surfaces were the largest factor in the decline of serve and volley since 2000, the event was played on the fastest surface of a Masters 1000 event, the indoor courts of the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy. Beyond these 3, most of the remaining top 10 are notable for their total absence of any serve-volleying. This is in contrast to 2000, when the year-end top 10 mostly had the will and ability to change things up with serve and volley, if only occasionally. Nadal tried it successfully a couple of times against Denis Istomin at Queen’s Club 2010, to the great surprise of all present, and the author knows of no other occasions. For Nadal, every point in every competition matters, whatever the score, so unlike Federer he is rarely or never ‘just playing’ with an opponent he has well beaten. His baseline play is outstanding, and consequently there is seldom a situation where serving and volleying will tilt the odds in his favour more than staying at the baseline – so to prevent any wasted points, he never serve-volleys. Djokovic uses it very rarely as a surprise tactic, but it is a trivial aspect of his game. Berdych, like Nadal, has been known to serve and volley (ineffectually) on grass courts, but again it is essentially non-existent. Soderling never serve-volleys despite his 140mph+ serve. Ferrer, Del Potro and Verdasco are much the same[5]. Just outside the consistent top 10, there are a number of players who incorporate serve and volley as a non-trivial aspect of their game. Tsonga used it occasionally to great effect to reach the final of the 2008 Australian Open, as did Mardy Fish in his 2008 US Open run. Jurgen Melzer, too, can use it as an effective change-up, helping him reach the 2010 Wimbledon fourth round. To find other true serve-volleyers, further climb-downs in the rankings are necessary[6]. Here, three main categories of modern serve and volley emerge. The first, dwindling group are veterans from the 90s and early 2000s. Llodra (30 years old) and Stepanek (32 years old) are the main players in this category, following the retirement of Dent in 2010. The second are doubles specialists. Naturally suited to playing at the net and practised at serve-volleying, doubles specialists often trade on this unusual advantage when entering singles – a good example is Nicolas Mahut. And thirdly, are big (and usually tall) servers. Thus Ivo Karlovic usually follows his record-breaking serves to the net, as does the 6’7” Chris Guccione. But even armed with the biggest serves with the acutest angles in the game, younger tall players such as Kevin Anderson and John Isner frequently elect to stay back on serve. The remaining reserves are in doubles play proper, where serve and volley remains a winning tactic at the very highest level, and a few of the 1,000+ professional journeymen singles players that play in Challengers and Futures level events across the globe. Indeed, it is worth noting that outside the very top 0.0001% of tennis players in the world, pure serve and volley remains a viable tactic. Llodra, after all, is the 24th best player on the entire planet. Thus unknowns like Takao Suzuki, Prakash Amritraj and Ivan Navarro can quietly ply their trade, winning enough matches to earn a living, and, very rarely, making enough of a run in a major tournament to feature as a brief blip on the radar of tennis spectators everywhere. So what is the future of serve and volley? As a surprise tactic, it appears to remain safe. Two of the most prominent breakthroughs of 2011, Milos Raonic and Ryan Harrison, are competent serve -volleyers. Both players clearly practice the tactic as necessary, for one can be a great server and a great volleyer and yet be ineffectual at putting these together in serve and volley – look at the tenuous footwork of Djokovic on his rare attempts at serve and volley, compared to the fluid, razor-sharp mastery of Sampras. It of course helps that players like Raonic grew up idolizing Sampras. Without a similar influence around in the 2000s, it will be interesting to see whether many young players will feel inspired to put the dedicated time in necessary – Nick Bolletieri[7] says it takes three to four years to learn serve and volley well. Further, Bolletieri tells us it can take a talented player until their early twenties to master serve and volley– when college tennis scholarships are on the line, this is too late, as a player could instead be mastering a more straightforward baseline game likely to garner more wins. A few predict the return of a new, great serve and volleyer, almost as a Messianic figure sent to save tennis from its baseline tedium. Thus McEnroe foresees an ultra-athletic player that will serve and volley, and start beating the baseliners. Sampras, too, believes that his game would continue to work well against modern players. But this view is in the minority. Federer, a talented serve and volleyer, knew that the age was at an end, and changed in time to be a great all-court player. Dent and Henman both attempted to re-work their games much later in their careers to a more all-court focus, with less success. Indeed, a weary Dent came to say at the end of his career “serve and volley is not a viable way to play tennis – you have to serve aces to make it work”. For those desperate for a glimmer of hope for a future tennis containing serve and volleyers, perhaps one thing can be said – should serve and volley ever become viable again through changes to courts or racket technology etc., it will come to the fore again, perhaps discovered by a lowly ranked singles player, or a doubles specialist causally playing a singles tournament. For now – quasi-religious predictions of a resurrection aside –we can see that Bjorkman was right in 2001. Top-ranking serve and volleyers have died. And tennis has died quite a lot, too. [2] http://www.tennisserver.com/photofeed/2010/100816-wsfg_mens_masters.shtml [3] It is worth noting that the All-England Club officially denies that the changes in surface and balls during 2001 were at all significant, and that there was no intention to change the surface for a particular style of play. This being so, it becomes difficult to explain the dramatic difference in play that prevailed after that point, so their claims are at best open to question. [4] http://2010.wimbledon.org/en_GB/news/interviews/2010-06-28/201006281277741945488.html [5] All players will run into the net to volley away a return that flies very high into the air, but this ‘serve, see high return, and come to the net to volley it away’ is not true serve and volley, which is a premeditated tactic known to the server before they even hit the ball. [6] Even amongst the ‘serve and volleyers’ named here, some have changed their playing styles over the course of their careers, and adapt their play for more or less serve and volley dependent on surface, opponent &c. [7] http://www.midatlantic.usta.com/will_the_serve_and_volley_ever_bounce_back/ Postscript: Since writing this article, Wimbledon 2011 saw a small but significant amount of serve and volley tactics. Murray, Tsonga, Fish and Lopez all serve and volleyed on their runs to the quarter-finals (and Del Potro, surprisingly, used the tactic up to the fourth round). Indeed, Roddick vs Lopez was a true blast from the past, a wonderful mix of serve-volleying, chip and charge, net-attacking tennis as well as the usual baseline battles. The situation in the final between Djokovic and Nadal, however, remained starkly different to the serve and volley of the 2001 final a decade ago. Nonetheless, Djokovic did serve and volley out of nowhere to set-up championship point – suggesting that serve and volley, as a surprise tactic, is indeed here to stay.  The change in the tournament overall was mirrored in the change in a man, Roger Federer. Though he serve-volleyed extensively in his final against Philippoussis in 2003, he never again attacked as much as he did in 2001 against Sampras. In his subsequent finals against Roddick and Nadal, Federer primarily made his impact from the baseline, serve-volleying infrequently. In a 2010 interview[4], Federer remarked that “I obviously came here in the year when I played Sampras, let’s say, I was serve and volleying 80% of the first serve, 50% on the second serve. I remember once speaking to Wayne Ferreira who I was playing doubles with that year actually. He said he used to serve and volley always first serve, 50% of the second serve. And towards the end of his career at Wimbledon, he used to serve and volley 50% of his first serve and not anymore on his second serve. You wonder, how in the world has that happened? Have we become such incredible return players or can we not volley anymore or is it just a combination of slower balls, slower courts? I think it’s definitely a bit of a combination of many things. If I look back, I think we definitely had many more great volley players in the game back then. When you do have that, you are forced to move in, as well, because you don’t want to hit passing shots against a great volleyer over and over again. But because we don’t have that as much anymore, everybody’s content staying at the baseline”

The change in the tournament overall was mirrored in the change in a man, Roger Federer. Though he serve-volleyed extensively in his final against Philippoussis in 2003, he never again attacked as much as he did in 2001 against Sampras. In his subsequent finals against Roddick and Nadal, Federer primarily made his impact from the baseline, serve-volleying infrequently. In a 2010 interview[4], Federer remarked that “I obviously came here in the year when I played Sampras, let’s say, I was serve and volleying 80% of the first serve, 50% on the second serve. I remember once speaking to Wayne Ferreira who I was playing doubles with that year actually. He said he used to serve and volley always first serve, 50% of the second serve. And towards the end of his career at Wimbledon, he used to serve and volley 50% of his first serve and not anymore on his second serve. You wonder, how in the world has that happened? Have we become such incredible return players or can we not volley anymore or is it just a combination of slower balls, slower courts? I think it’s definitely a bit of a combination of many things. If I look back, I think we definitely had many more great volley players in the game back then. When you do have that, you are forced to move in, as well, because you don’t want to hit passing shots against a great volleyer over and over again. But because we don’t have that as much anymore, everybody’s content staying at the baseline” But only when climbing down to the rank of 24 in the world do you hit the first true serve-volleyer, Michael Llodra. A tricky lefty and doubles Grand Slam champion, with a serve branded ‘unbelievable’ and volleys which are ‘the best on the tour’ by Robin Soderling, he has been making some inroads into Grand Slams and Masters 1000 events – notably a semi-final run on the quick fastcourts at Paris, where he was only just edged by the much higher ranked Soderling. He has claimed some remarkable scalps including Querrey, Berdych and Djokovic. He is, in his own words, ‘like the Last of the Mohicans’, and the rarity of his game can cause some opponents to unravel. But not all. The great test of his game came in the crucial 2010 singles Davis Cup tie between France and Serbia. There, the unfazed baseliner Victor Troicki efficiently and consistently unlocked Llodra. Whether it is the rackets, the surface, or the athleticism of players, few tennis fans could have seen this as anything other than a final, superfluous nail in the coffin of serve and volley at the highest level.

But only when climbing down to the rank of 24 in the world do you hit the first true serve-volleyer, Michael Llodra. A tricky lefty and doubles Grand Slam champion, with a serve branded ‘unbelievable’ and volleys which are ‘the best on the tour’ by Robin Soderling, he has been making some inroads into Grand Slams and Masters 1000 events – notably a semi-final run on the quick fastcourts at Paris, where he was only just edged by the much higher ranked Soderling. He has claimed some remarkable scalps including Querrey, Berdych and Djokovic. He is, in his own words, ‘like the Last of the Mohicans’, and the rarity of his game can cause some opponents to unravel. But not all. The great test of his game came in the crucial 2010 singles Davis Cup tie between France and Serbia. There, the unfazed baseliner Victor Troicki efficiently and consistently unlocked Llodra. Whether it is the rackets, the surface, or the athleticism of players, few tennis fans could have seen this as anything other than a final, superfluous nail in the coffin of serve and volley at the highest level.

[1] This discussion is especially indebted to Ian Westermann’s ‘Miss Serve and Volley? Get Over It’ at the Essential Tennis ProBlog.